Riding Mill is bidding to raise funds to put right a mistake on its war memorial which went unnoticed for eight decades – can you help?

Riding Mill is bidding to raise funds to put right a mistake on its war memorial which went unnoticed for eight decades – can you help?

Crowdfunder appeal – click here

The memorial across the road from St James’ Church, in Riding Mill, bears the names of those men from the parish who lost their lives in both world wars.

But for some unknown reason the inscription for Frederick Best, who died as a prisoner of war in 1942 at the age of 29, wrongly indicates he served with the RAF. In fact, he served with the British Army in North Africa, as a sapper with the Royal Engineers.

Now, approaching the 80th anniversary of his death, and ahead of this year’s Remembrance Sunday on November 13, the village has launched an appeal to find money to alter the inscription.

The mistake on the plaque was only revealed recently by former churchwarden Sandy Gardner. Each Remembrance Sunday, he read out the names of the men from the village who lost their lives in both wars.

For the centenary of the end of World War One in 2018, he decided to find out the Christian names of those who died, so he could read out their full names rather than just their initials.

The research proved straightforward for every name, apart from that of FDK. Best.

Extensive inquiries with the RAF drew a blank. Only after calling on the help of village history enthusiast Susan Law did it come to light that Sapper Best served with the Royal Engineers, and that the inscription on the memorial had been wrong since it was added at the end of World War Two.

Now the village is embarking on an appeal to raise enough money to employ a specialist to make the alteration.

“My father was with the Royal Engineers during World War Two, so I know all too well how proud men were to serve with the Royal Engineers,” said Sandy.

“It is important we do the right thing by Frederick Best, and make the correction to the memorial. It is the least we can do in honour of a young man from the village who made the ultimate sacrifice for King and Country.”

Those who want to contribute to the appeal can do so online www.crowdfunder.co.uk/p/war-memorial-correction

In addition, the parish council is keen to hear from any descendants of Sapper Best. They may help in piecing together more of his life story and family background, as well as be guests of honour at a rededication of the memorial when the amendment to the inscription is made, hopefully in time for next year’s Remembrance Service.

Anyone with information can email the parish council clerk Catherine Harrison at ridingmillclerk@gmail.com

TRAGIC JOURNEY FROM THE BANKS OF THE TYNE TO A FINAL RESTING PLACE IN MILAN

A PRISTINE white cross towers in solemnity over an immaculately manicured lawn on the outskirts of Milan.

The so-called Cross of Sacrifice, illuminated on its octagonal plinth by the Italian sun, is the centrepiece of a military cemetery marked out regimentally by 31 razor sharp lines of identically shaped white headstones, where the remains of 417 British and Commonwealth servicemen are interred.

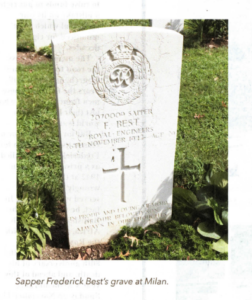

Amidst the hushed ranks of the Fallen, one headstone reads; “Sapper F. Best, Royal Engineers, 26th November 1942 – age 29.”

Then, under a simply carved cross, there is a poignant and deeply personal inscription: “In proud and loving memory of our beloved son. Always in our thoughts.”

The only indication of his home village 1,000 miles away lies within the cemetery register, which records Sapper Best as the son of John and Annie Best, of Riding Mill, Northumberland. The inscription, one can presume, was included at their request.

That the body of Sapper Best, from Riding Mill, lies in this peaceful corner of Italy’s second biggest city is the only certain fact known about him.

His childhood, upbringing, working career, army service, exact wartime activities and death all remain somewhat vague; matters of conjecture shrouded by the mists of time and the fog of war.

But it has been possible to map out a sketchy outline of his tragically short life.

Frederick Best was born in 1913, the second youngest of five children to John and Annie. According to the 1921 census John was a chauffeur at Stelling Hall, at Newton. But is known the family subsequently moved to Riding Mill, and were living there during the war.

Nothing is known of young Frederick’s education, or his profession. But it is likely he became a skilled tradesman, which would have enabled him to take up service with the Royal Engineers.

He was a sapper with the 235th Field Park Company of the Royal Engineers, which recruited largely from Northumberland, Tyneside and the Tyne Valley.

When he enlisted is unknown. However, if he joined at the start of hostilities, it is possible he was with the Company, part of the 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division, when it was evacuated from Dunkirk in 1940 as part of the British Expeditionary Force.

He would almost certainly have been with the Company in May 1941 when it embarked on a troop carrier bound for Egypt, via the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa.

Later that summer the Company head for Cyprus, before arriving in Palestine in January 1942, then to Syria, back to Egypt, before a fateful positing to the Western Desert Campaign in North Africa by Spring.

On May 26, Axis forces led by Rommel attacked the Gazala Line, in Libya, defended by in the region of 100,000 Allied troops, including Sapper Best and the 235th Field Park Company.

With two days Rommel overran the Allied defences and the 235th Company was captured.

Official Army records list Sapper Best as ‘missing’ on May 30. Later, records are amended to list him as a Prisoner of War.

PoWs were handed over to the Italians and transported to the port of Derna, on Libya’s Mediterranean coast. From there they were shipped to port of Taranto, in Puglia, in Southern Italy.

From Taranto the PoWs were moved to holding camps. It is recorded that some members of the 235th Company were held at a camp at Macerata. This was a large camp, established in the summer of 1942 on the site of a disused linen factory. Sanitation was poor, with only 12 toilets and three taps for the 10,000 prisoners held there.

It is most likely Sapper Best was imprisoned there, before being moved on to more permanent camps.

Sapper Best’s scant war records have him as a PoW at Camp Fossoli of Carpi, near the historic city of Modena, in northern Italy.

Although it has been impossible to verify categorically, it is most probable Sapper Best died there on November 26

The cause of his death is unknown, and can only be a matter of conjecture. He could have been wounded in the Western Desert campaign and died as a result of his injuries.

However, many more PoWs in Italy died as a consequence of malnutrition or poor sanitation in hastily constructed camps starved of meaningful Red Cross supplies until the winter of 1942.

Sapper Best’s remains would have been buried in a makeshift grave at the camp where he died, and only transferred to the cemetery at Milan after the end of the war in May 1945.